Friedman’s Shareholder Theory

Milton Friedman’s Shareholder Theory asserts that the primary responsibility of a business is to maximise profits for its shareholders. Friedman argued that businesses are essentially tools of their owners (the shareholders) and should focus exclusively on generating the highest possible returns, provided they operate within the bounds of law and ethical norms. This perspective, articulated in his famous 1970 New York Times essay, “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits,” has become a cornerstone of modern corporate governance theory.

Friedman contended that when businesses engage in social responsibilities beyond profit-making—such as investing in employee welfare or environmental initiatives—they are, in effect, imposing a form of taxation and deciding how to allocate resources without democratic legitimacy. He maintained that corporate executives who pursue social objectives are spending other people’s money without proper authority. In addition, he believed this distracts from the core purpose of business and represents an inefficient use of resources.

Stakeholder Theory

In contrast, the Stakeholder Theory, championed by R. Edward Freeman in the 1980s, posits that businesses have responsibilities not just to shareholders but to all stakeholders. Stakeholders include anyone affected by the business—employees, customers, suppliers, communities, and the environment. According to this view, companies should create value for all these groups, balancing their interests rather than focusing solely on maximizing shareholder profits.

Stakeholder Theory suggests that businesses should consider the broader impacts of their decisions, prioritising employee well-being, sustainable environmental practices, and fair treatment of suppliers—even if it doesn’t result in immediate profit maximisation. Proponents argue that this approach creates more resilient businesses with stronger relationships across their value chain, ultimately leading to more sustainable long-term success and societal benefit.

The obfuscation of performance by the Stakeholder Theory

While Stakeholder Theory has gained traction in recent years, I lean toward the clarity offered by the Shareholder Theory as an objective for corporate management.

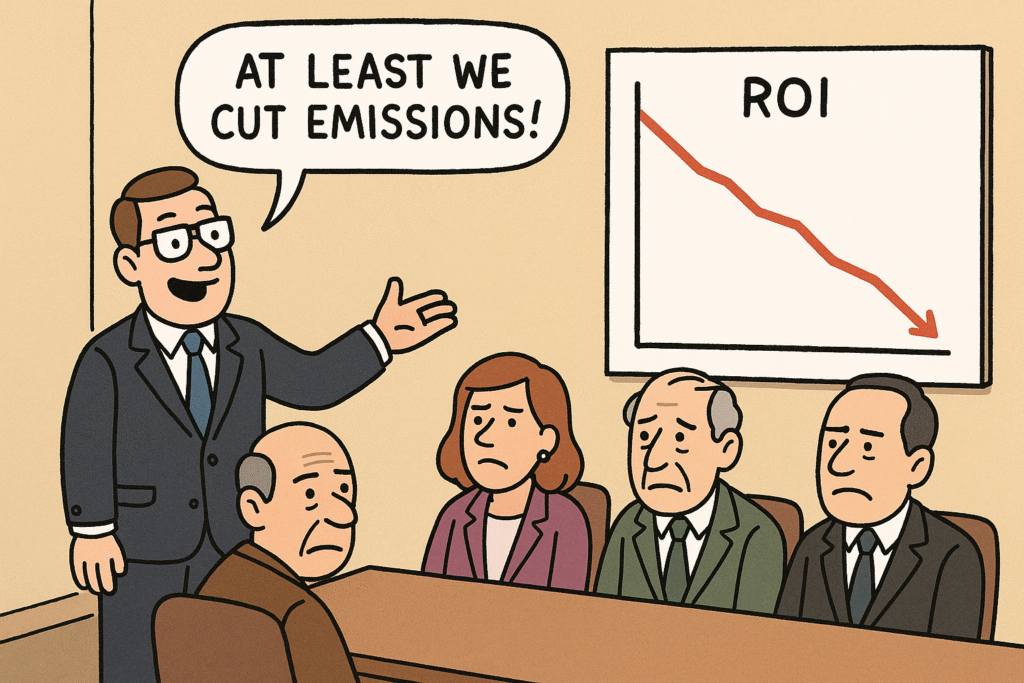

Profit is a direct metric that allows shareholders to judge the performance of management. The more metrics a management team brings in, the harder it is to compare different managers to ensure shareholders are hiring the right people. This multiplication of success criteria can create a scenario where underperforming executives justify their results by cherry-picking favourable metrics while downplaying financial underperformance.

A singular focus on ESG can detract from a company’s financial performance. Profit-making provides a simple and objective measure of success. For example, how much profit should shareholders be willing to sacrifice to achieve a 20% reduction in carbon emissions? This question becomes particularly thorny when considering that different shareholders may have vastly different values and priorities. From a Shareholder Theory perspective, Stakeholder Theory could potentially allow management to justify underperformance by shifting focus away from profitability.

Many of the world’s problems, such as those stemming from the tragedy of the commons, should not be left to business proactivity. The impact of each individual business is limited, and decisions to engage in social good can reduce competitiveness. For instance, if an asset manager like BlackRock accepts lower returns by restricting its investment portfolio to ESG-compliant stocks, another fund may capitalise on this by attracting clients with the promise of higher returns, thereby undermining BlackRock’s market position. This competitive dynamic creates a race to the bottom where ethical considerations may be sacrificed for market share.

Imagine if you were hiring a plumber. The sole metric you use would be whether the plumber successfully fixes the leak in your home. It would make it very difficult if you wanted to compare how plumbers treated their workers, or the amount of scope 3 emissions produced in their works. Similarly, companies should prioritise profitability as a clear metric of success, leaving other concerns to be addressed by government policies.

Property rights should be respected

Social good, in my view, is primarily the responsibility of the government, which is accountable to the public. Companies are owned as assets that are expected to reap a return – this is the only certain thing that investors would expect. Just because an ESG fund announces their support for a smelting company to pursue lower emissions, doesn’t mean that a small retail investor in the company cares about the same cause. Just as you wouldn’t expect your personal property to be repurposed for societal benefit, companies should not be expected to divert funds away from their owners for social causes.

As such, management runs the risk of failing to meet their fiduciary duty by engaging in activities outside of profit-seeking. Hypothetically, if a CEO of Coca-Cola were to donate $1 billion in company funds to animal welfare, they would be unilaterally diverting shareholder money toward a cause that might not align with all their investor priorities. Maybe a shareholder would prefer to have received that cash in dividends and spent it on an orphanage instead. This highlights the problematic nature of corporate executives making moral decisions on behalf of diverse shareholders with varying values and priorities. American Airlines was found by a judge to have violated its duty to maximise financial returns by entrusting its pension scheme to BlackRock and allowing it to use ESG factors as an investing guide. In order for companies to meet their fiduciary duty, ESG can only safely be pursued as a by-product to higher returns, and not at the expense of shareholders.

A counter argument to this would be when the cost to the company to align with ESG goals is much lower than for external parties who receive dividends from the company. For instance, an oil pipeline company would find it cheaper to ensure regular maintenance of their pipeline, than their shareholders would find it cheaper to clean up an oil spill. Yet, companies may delay preventive measures to preserve short-term profits. This short-termism can lead to decisions that are ultimately value-destroying even from a purely financial perspective. That said, the best way forward would be to penalise oil spills, such that the company is aligned in prevention from the standpoint of profit-maximisation. That brings us to structural changes in the business environment.

Structural changes to align the stakeholder welfare and profitability

Worker empowerment: According to Shareholder Theory, a company should not be responsible for looking after employees beyond what is necessary to meet legal obligations. Instead, workers should be empowered to increase their bargaining power through unions or collective action. This approach shifts the responsibility for worker advocacy onto the employees themselves, rather than relying on corporate benevolence. Of course, this must be balanced with competition laws to prevent both unions and companies from abusing dominant positions. If companies find that treating their employees well and paying fair market wages improves retention and labor relations, they will naturally choose to do so of their own accord, motivated by the potential for higher profitability.

Pricing in externalities: This approach ensures that businesses remain profit-driven but do so in a way that reflects the true social cost of their operations. Instead of relying on voluntary corporate goodwill, well-designed policies incentivise innovation and cost-efficiency in addressing issues like climate change. For example, a carbon tax doesn’t dictate how a company should reduce its emissions—it simply encourages businesses to find the most efficient path to compliance. This allows the “Invisible Hand” of the market to function within a framework shaped by the “visible hand” of government regulation.

The Role of Regulations

Instead of expecting businesses to self-regulate for the public good, the key lies in strong, well-enforced regulations. Governments must shape the space in which businesses operate, creating a level playing field that ensures all companies adhere to standards for environmental protection, labor rights, and corporate governance. This approach allows businesses to focus on profit-making within a clearly defined framework that aligns with societal goals.

Ultimately, the debate between Friedman’s Shareholder Theory and Freeman’s Stakeholder Theory ultimately hinges on where we believe responsibility for societal good should lie. While Stakeholder Theory appeals to the broader interests of society, I argue that the role of addressing social and environmental challenges is best reserved for governments, not corporations. Businesses should focus on what they do best—driving innovation, creating wealth, and delivering value to their shareholders—within a robust regulatory framework that ensures they operate responsibly. Strong and impartial governance is the linchpin in this equation, ensuring that societal objectives are met without diluting corporate focus or undermining competitive markets. By combining strong governance with corporate focus, we can achieve a balance that fosters both economic growth and societal well-being.