Elon Musk famously claims to sleep and live in his factories to work longer hours and drive his companies forward. This relentless dedication has paid off for him; he is now one of the wealthiest people on the planet. However, the same can’t be said for everyone. Take Nico Murillo, for example—he followed a similar approach, sleeping in his car and showering at the factory, but after four years at Tesla, he was fired. Hard work doesn’t always pay off for a worker.

This disparity highlights a harsh reality: employees, as suppliers of labor, are held to unrealistic expectations. In almost every industry, businesses routinely raise prices in line with inflation without a corresponding increase in product quality. Yet, workers are often expected to improve their output, skillset, and commitment, with only marginal increases in compensation—if any at all.

Some companies go so far as to demand “entrepreneurial employees,” a term that, on closer inspection, is an oxymoron. It’s a way to squeeze effort, creativity, and initiative while offering employees a minuscule share of the resulting profits. The less you profit from your company’s success, the less of your entrepreneurial spirit you should share. Save that energy for ventures that truly belong to you.

Individual Rationality and Incentive Compatibility

Individual rationality ensures both candidates and employers find value in the job agreement: candidates take the job, and employers hire them.

Incentive compatibility ensures candidates showcase their real skills and employers are honest about job expectations.

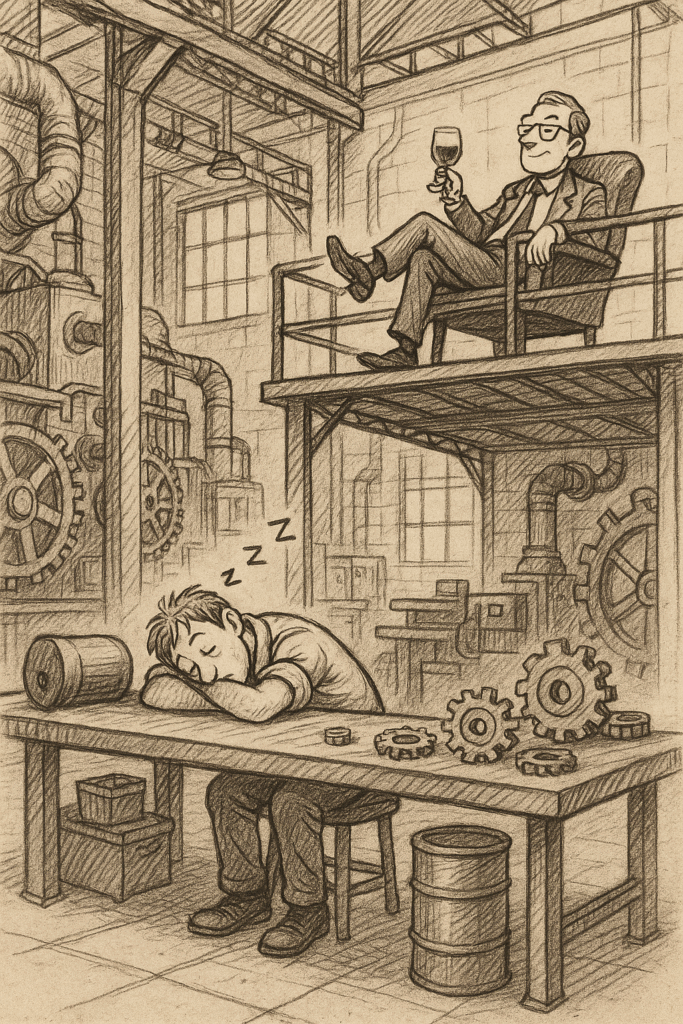

An employer cannot directly observe the level of effort an employee puts in, especially in white collar roles where output is not easily quantified. Think about how many managers push paper and claim the credit for work their underlings do while they’re out playing golf.

Employees would prefer to skive, or do a side hustle that brings in money, rather than work hard to make their employers dream a reality. The only thing that prevents that on a fixed wage basis is the fear of being discovered and fired.

Employers can however monitor the level of profit they get, which is influenced by the effort put in by the worker – high effort translates to more sales done. Maybe even lower costs, if the worker starts cooking chicken in a hotel kettle to avoid expensing dinner (please don’t ever do this!).

As an academic question, the employer can technically choose to profit-share with employees, which comes as a bonus (a % of profits), if effort on the employees part can materially increase the level of profit enjoyed by the employer – even after deducting the employee’s cut. This then poses a very fun economics conundrum – how much would a manager have to pay to ensure best effort by the worker, yet makes sense. In certain cases, employers might find it rational to just hire a worker but not pay them above their reservation wage (the wage they would get outside the job), because the cost of enforcing higher effort is just too high to justify.

Outside of small companies and theoretical exercises, however, few employees have the ability to directly influence the profit and loss of a company and hence bonuses are unlikely to drive direct effort.

As such, employers instead wield psychology instead of economic theory. Rather than incentivise, they use shaming and cajole employees with “personal development” from taking on more responsibility at work.

“Quiet Quitting”

In 2022–2023, the trend of “quiet quitting” emerged, where employees did only what was expected of them, refusing to go above and beyond. This was met with shock and disdain from many quarters, yet it’s hardly different from how companies behave with their customers.

When I buy 100 grams of minced beef, I don’t expect to find 150 grams in the package. We’re quite content when businesses give us exactly what we pay for—no more, no less. Why should the employee-employer relationship be any different? I find it hilarious, if not a little tragic, that it has become so normalised to be expected to do your best instead of working to expectations.

Of course, the reality is that if you quiet quit while others in your team go the extra mile, they’re likely to be promoted before you, assuming both of you are equally visible to leadership. But therein lies an important point: visibility often matters more than hard work. It’s not about burning out to prove your worth; it’s about maximizing the time spent in positions of influence and recognition.

I’m not advocating that you rest on your laurels, and spend the time away from work sipping on cocktails in the Maldives, simply because that’s not what I would do*. For those of us who are habitual workaholics, push hard if you are confident that the work will be rewarded with higher compensation. If the reward of going above and beyond is simply more work, I’d advise that you put that energy and focus into a second job, or a side-hustle that you’ve always wanted to build.

Give your all for your own life

It’s important to recognize two things: 1) your employer may not always appreciate or reward the extra effort, and 2) your day job is not your only avenue for growth, learning, or even income.

Your career is just one avenue of growth. In today’s world, diversifying your energy, time, and creativity can be much more rewarding than pouring it all into a single job. Be strategic with your effort. Work hard when it counts but conserve enough of yourself to explore pursuits that can lead to true personal and financial growth—outside of the confines of your current employer.

In the end, the question isn’t whether you should give your all—it’s who you should give it to. Your employer? Or yourself?

*That said, I must admit that I am very jealous of folks who can really disconnect and enjoy a vacation – it’s something I’m working on as a New Year Resolution.