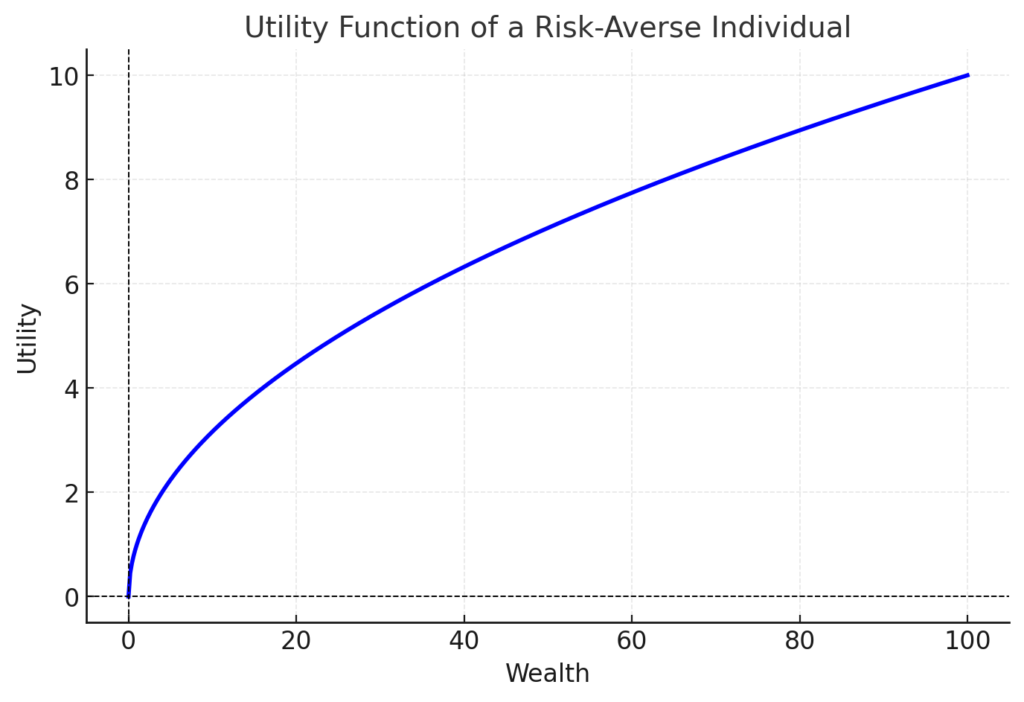

Humans are inherently risk-averse. This means that, when presented with a choice, most people tend to prefer a certain, lower reward over a higher potential reward that comes with greater risk.

The St Petersburg Principle involves a hypothetical game where a fair coin is flipped until it lands heads. The payout for the game doubles with each toss, starting at $2 for one toss, $4 for two tosses, $8 for three, and so on. Would you pay $100 to play this game? Would you pay $100 to play? On paper, the expected value of this game is infinite—yet most people would hesitate to pay even $20. Why? The paradox arises because the infinite expected value clashes with diminishing marginal utility: as the payout grows, the additional value of money becomes less meaningful to individuals.

Insurance vs gambling

Diminishing marginal utility means that it is possible that fully rational individuals buy insurance willingly while insurance companies continue to rake in profits. Insurance provides certainty and protection against potential financial losses, aligning with risk-averse behaviour. For risk-averse individuals, the utility derived from a guaranteed, smaller loss (the insurance premium) is greater than the disutility of a potentially large, uncertain loss, even if the expected wealth without insurance is mathematically higher.

Despite this aversion, people frequently engage in gambling where the expected value is less than 1. Funnily enough, it seems like people do pay to undertake risk.

Take a common casino game like roulette. In American roulette, the wheel has 38 slots—18 red, 18 black, and 2 green (0 and 00). Because the house has built in 2 greens to better their own odds, you only have a 47.4% chance of winning. So for every dollar you bet, you can expect to lose 5.3 cents in the long run. The house collects the expected value, and all the gambler receives is the volatility of uncertainty rather than hedging against risk.

Yet, gambling persists, not because it’s a sound financial decision, but because of the emotional payoff. People see it as entertainment, a way of buying hope—the hope of striking it big with a jackpot or a string of wins. This is the key utility gamblers seek. But what if you reframed the question: What is your utility compared to buying your BATNA (Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement)? If the expected loss from gambling is $50, what else could that $50 buy in terms of tangible enjoyment, security, or even growth?

The utility of gambling vs. risky investments

Of course, gambling has its merits—people aren’t just throwing their money away; they are consuming a service that provides entertainment and excitement. It’s almost like paying through the nose for bungee jumping in the pursuit of adrenaline. However, I’d argue that if the thrill is the primary goal, you might consider risky investments on well-regulated exchanges instead. This could be a more productive outlet to fill the desire for risk-taking, especially since these investments often offer a positive expected value.

Unlike gambling, where the house always has an edge, the expected value of a carefully chosen stock can be favourable. It is not a zero-sum game, but a case of funds being used for value creation. Yes, the stock market has its risks, but a company’s performance isn’t predicated on rigged odds—management is striving for growth, creating value for shareholders. Even short-sellers who bet against companies don’t change the company’s inherent value. Instead of wagering against mathematically stacked odds, you are riding on the promise and efforts of the company’s management.

For example, small-cap stocks, which are stocks of companies with a relatively small market capitalisation, often carry more volatility but also more room for growth. The small-cap premium (Banz, 1981) came from the realisation that smaller companies tended to generate higher average returns than larger ones. This could be seen as compensation for the higher risk faced by investors in these stocks.

Risk management: treat risky investing like gambling

That said, risky investments should still be approached with the same caution as gambling. Just as you wouldn’t walk into a casino and place your life savings on red, you shouldn’t allocate a significant portion of your portfolio to speculative stocks. Instead, it would be wise to allocate only a small fraction of your wealth to these types of investments—an amount you can comfortably lose without feeling the financial sting. Consider it “play money,” akin to a gambling budget.

By taking this approach, you can still enjoy the thrill of uncertainty and the potential for large gains, but with the added benefit of a positive expected value. In contrast to gambling, where the expected outcome is a guaranteed long-term loss, the stock market allows for the possibility of a win-win: even if your risky investment doesn’t pay off, your losses are limited, but the potential for gains is real.

Ultimately, whether through gambling or investing, risk-seeking behaviour is a part of human nature. The key is to channel that behaviour into avenues where the odds are more in your favour—where risk has the potential to lead to reward, rather than just entertainment.