Is a university degree still worth it? For many in Gen Z, the question feels more urgent than ever. Despite skyrocketing tuition fees and growing student debt, university enrolment continues to rise, with a seemingly zero price elasticity of demand. On the surface, this makes sense—higher education has traditionally been seen as the path to better jobs and brighter futures. But beneath this narrative lies a growing inefficiency in the system.

At Oxford, the microeconomics module broke down this phenomenon: When degrees function as a form of educational signalling. It was such a meta experience, to be sitting in an Oxford tutorial explaining why I was such paying a eye-watering amount for a degree without clear tangible benefits.

A university education traditionally offers two distinct benefits:

- Capability building – improving skills and knowledge

- Signalling – acting as proof of an individual’s ability to succeed

The problems begin when the former benefit is negligible, and the latter holds an outsized weightage. The problem compounds when the cost of this signalling increases significantly.

Adverse selection: Signalling

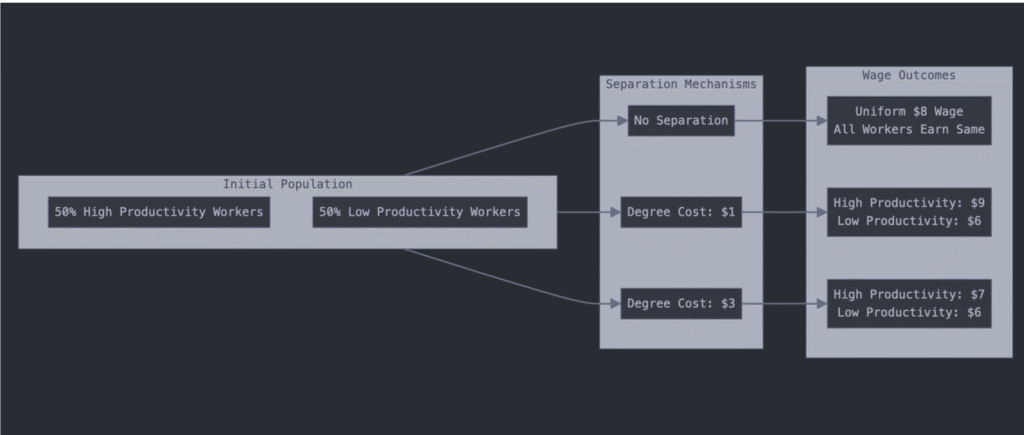

We start by simplifying the population into high and low productivity types in equal proportion. The productivity level cannot be observed by employers directly (maybe after they’ve hired the worker, but it’s still difficult to directly observe and the employer has to incur high hiring and firing costs). Obviously, candidates are going to claim that they are high-productivity in an interview, so employers can’t just ask them.

In such a scenario, employers would offer an average wage, calculated as:

For instance, if those who are high productivity are worth $10 but those who are low productivity are worth $6. Without a separating mechanism, the wage for all would be ($10+$6)/2 = $8 for all.

As such, the high-productivity ones would like to signal their type to get a higher wage, while the low-productivity ones want to hide it to avoid a lower wage. A signal for the high productivity types would hence have to be rational for the high productivity types to implement but costly for the low-productivity types.

That is why a degree is seen as a signal: There is an assumption that the high-productivity types will be able to graduate while the low-productivity types are either unable to do so or have to undergo a costly process to achieve it.

Let’s assume a degree costs $X for a high-productive individual to attain and is completely unattainable for low-productivity types.

If X =1, the high productivity individual benefits by getting a degree. By getting a degree, they signal they are high-productivity types. Employers hence pay them $10. Their net benefit is hence $10- $1 = $9. Low productivity individuals would rather opt out of this system – they can’t earn a degree! However, anyone without a degree would hence be class as a low-productivity type and be given $6 instead.

Now, the cost of degrees increase such that X=3.

Because an individual with no degree would only earn $6, a high-productivity individual would rather still rather get a degree – the net benefit is ($10 – $3) = $7.

In this case, both classes of workers act rationally but are worse off than if degrees did not exist. High productivity types earn $7 and low productivity types earn $6, compared to $8 for all if degrees did not exist.

The gap arises because resources are channelled into education signalling. Yet, no high-productivity agent can individually opt-out without taking a loss.

Real world implications

Of course, in the real world, a degree is meant to improve an individual’s productive capacity, which we ignore in this very sad example above. Unfortunately, an anecdotal trend I’ve seen in Oxford is the tendency of some students to take on degrees with questionable relevance to the working world. They do so with the confidence that the Oxford signal will help them get a job.

This can result in a sub-optimal outcome: The optimal path for people with that innate ability to work a corporate job is to get a degree to signal their competence. Yet, the immense cost of the degree is a burden that causes immense stress and the resulting student debt weighs on them as an anchor.

The above economic problem also assumes that people are able to decide rationally. Unlike an economic problem where agents act with perfect information, high-school graduates often make decisions without fully understanding the costs and benefits. Attending university feels like an unavoidable choice. Their parents, teachers, and society at large often view it as the default path to success. But the reality is more complex. They enter university expecting it to be a golden ticket, only to graduate into a labour market that undervalues their degree. Worse still, their parents’ experiences—when far fewer people attended university and degrees held greater value—fuel these misguided expectations.

The 2021-2024 period offers a cautionary tale. Students who began their degrees during the COVID-induced tech boom faced dramatically different job prospects upon graduation. The post-pandemic slowdown meant fewer opportunities, leaving many disillusioned about the value of their education.

Unfortunately, university enrolment has skyrocketed, raising the supply of graduates and depressing the wage for graduates. China is an illustrative example. The high focus on education has resulted in a deluge of fresh graduates, with a historic record of 11.7 million college students graduating in 2024. Meanwhile, the number of American graduates grew 80% over the 20 years from 2001-2021.

As the cost of signalling has increased, but the potential value of the signal has fallen, yet not sufficiently for it to be rational, the current generation of students are trapped in a sub-optimal solution.

The UK has increased the cap for full-time student fees by £285, and I am sure international student fees will only be set to increase further as they have been over the past few years. I guess we should look on the bright side and practice gratitude that UK education costs have not gone to such ludicrous levels as they have in the United States, without a tuition cap.

Why life is getting harder: A degree is necessary but insufficient

This is the crux of the college dilemma: A degree is no longer enough. It is still a necessary signal for many careers, but the return on investment is lower, and the promise of upward mobility through education alone is fading.

The promise of a university education as a panacea to economic sluggishness and a sufficient qualification for social mobility is fading. It’s a much lower overall ROI, albeit positive, and the contribution overall to society is collapsing.

To succeed in this new landscape, students need to go beyond the degree. Side hustles, internships, and self-directed learning are increasingly critical. Employers now value practical experience and unique skill sets as much as—if not more than—formal qualifications. A degree may open doors, but it’s what you do beyond the classroom that determines whether you walk through them.