Cost cutting is not ideal as a standalone project. It’s far too easy for a central bureaucrat to say – costs are too high, we need to trim it. It is immensely difficult to parse out which departments are overspending, and which are being responsible stewards of the company budget.

I’ve often seen corporate leaders implement cuts in budgets across the board. This is harmful, because it hurts the folks who were responsible previously and did all they could to trim the fat from company operations.

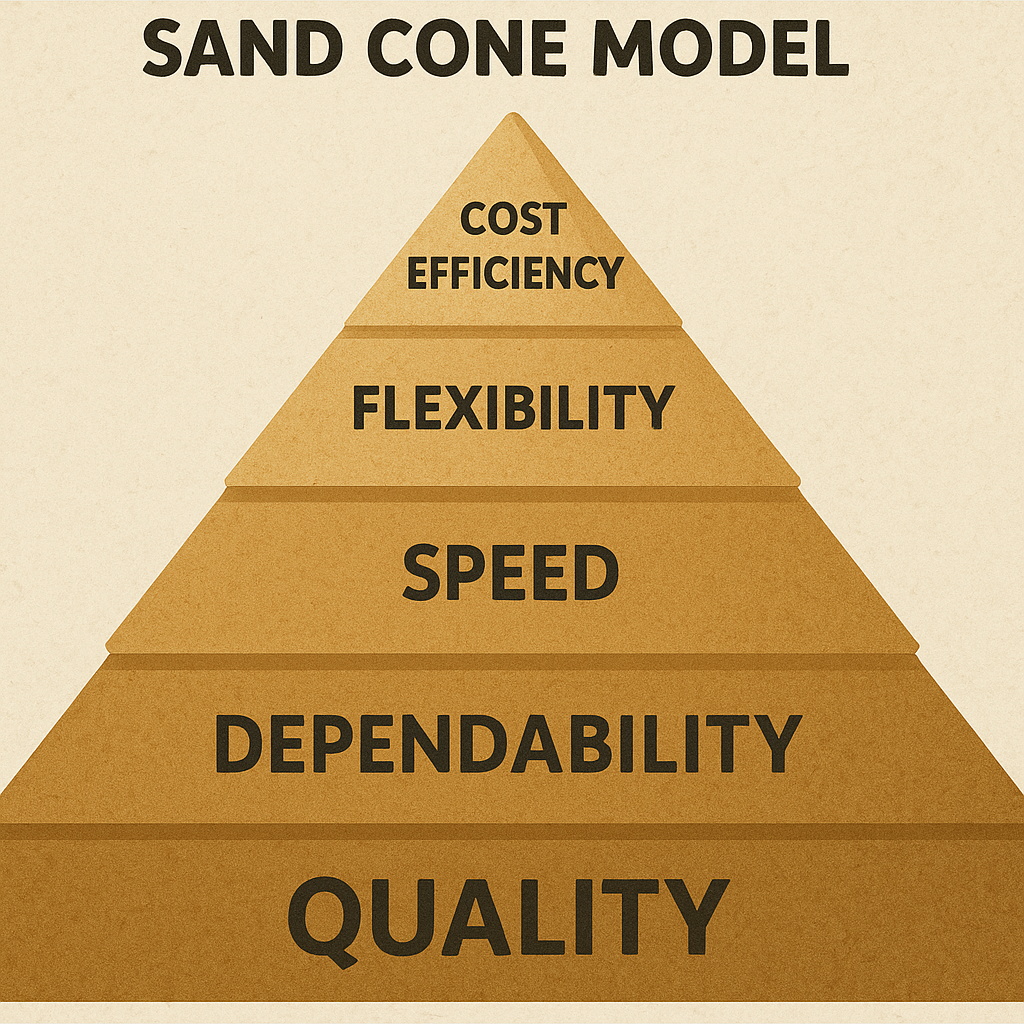

The Sandcone Model (Ferdows & De Meyer, 1990) posits that operational excellence builds cumulatively: first by ensuring quality, then dependability, followed by speed, and only then focusing on cost. Skipping or reversing this order risks undermining long-term competitiveness. It points to the trade-offs between the criteria for evaluating operations (cost, quality, dependability, speed, and flexibility), but argue that the criteria should be built in a specified order:

- Quality

- Dependability

- Speed

- Flexibility

- Cost

Cost will be last, because securing the initial three will help a company stand out. This is why I’m always immensely suspicious about cost-cutting. Top-down cost-cutting targets can be helpful when used as a spur to prompt employees to pay more attention to cost-controls. Managers unfortunately often reach for the cost-cutting lever indiscriminately though, because the results can be rapidly observed – more so than revenue targets – as expense line items are eliminated. However, compromises on quality, dependability, and other intangible measures are often less obvious, yet pose an insidious risk to the future prospects of the company.

IKEA is a company that has managed to navigate working on lean budgets while thriving. One deliberate policy is to set the price of the product and then design the product, instead of the other way around. However, this works because IKEA has set a name for itself by producing affordable furniture for the masses, and then leaned into its economies of scale as a defensive moat. Furthermore, many of their cost-cutting initiatives were innovations that improved the customer experience – flat-packing for instance not only lowered IKEA’s transportation and inventory costs, but also made it easier for the customer to bring home. Other cost-control measures, such as entertaining guests in IKEA cafeteria’s, not only saved costs without compromising on core product quality, but also incentivised better quality of food.

In contrast, Sears supermarket went bankrupt despite, and perhaps because of, aggressive cost-cutting. It moved towards cheaper and lower-quality products in a bid to cost-compete against Amazon, which alienated its customer base. Furthermore, investment in store maintenance was lowered and the customer experience suffered.

The economic slowdown as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and higher interest rates has rightfully put more focus on profitability rather than revenue growth. Still, I would always caution against celebrating managers who come swinging into an organisation promising to cut the fat and make operations more streamlined. It’s not easy to see when it’s not fat being cut out but vital muscle and flesh being removed that will result in a slow and painful death much later. Instead of indiscriminate cuts, companies should evaluate cost-saving opportunities through the lens of long-term operational priorities, as outlined by the Sandcone Model. This ensures cost-efficiency without sacrificing the pillars of quality and customer trust.