Game theory is about anticipating the reactions of the other party and making your move based on that reaction, projecting it out into the future. However, it is often reduced to iconic examples like the Prisoner’s Dilemma, a scenario so frequently cited that it risks trivialising the depth and breadth of this field. While the simplicity of the dilemma makes it accessible, it barely scratches the surface of what game theory can reveal about human behaviour, strategy, and decision-making. From corporate boardrooms to geopolitical standoffs, game theory provides a powerful lens through which to understand and navigate complex interactions and yield counter-intuitive solutions. When I first interviewed for the Economics and Management course, game theory felt interesting but limited. Hopefully, I get to pique your interest with what I’ve learnt here in the course, enough for you to delve deeper into this subject.

Chicken Game

Take the Chicken Game, a classic illustration of strategic brinkmanship. Imagine two drivers hurtling toward each other on a narrow road. Each must choose between two actions: to “swerve” or to “stay on course.” If both stay on course, they crash — the worst possible outcome for both. If one swerves while the other stays, the one who stays “wins” by appearing braver or more dominant, while the one who swerves “loses” by appearing weaker. If both swerve, neither “wins,” but they both avoid the catastrophic crash. The tension arises because each player must make their choice without knowing what the other will do, creating a dramatic standoff where each hopes the other will “chicken out” first.

The solution to the Chicken Game is counterintuitive yet brilliant: throw your steering wheel out of the window! By doing so, you signal unequivocally to your opponent that you cannot swerve, leaving them with no choice but to yield. This dramatic commitment alters the game’s dynamics, forcing your opponent to adjust their strategy.

This principle has immense practical implications in business. Consider factories investing in overcapacity. At first glance, such investments appear NPV-negative, as the market demand does not justify the excess capacity. However, the true purpose of this move is strategic. By demonstrating the ability to scale up production and depress prices, the company signals to potential entrants that entering the market would be unprofitable. The overcapacity acts as a deterrent, discouraging competition. In this sense, the investment isn’t merely a capital expenditure but a calculated fee to maintain market dominance and protect long-term profitability. This was used by Tesla when it invested in its gigafactories, signalling to the rest of the market that any competitive entry would be immediately unprofitable. This allowed Tesla to dominate the battery market.

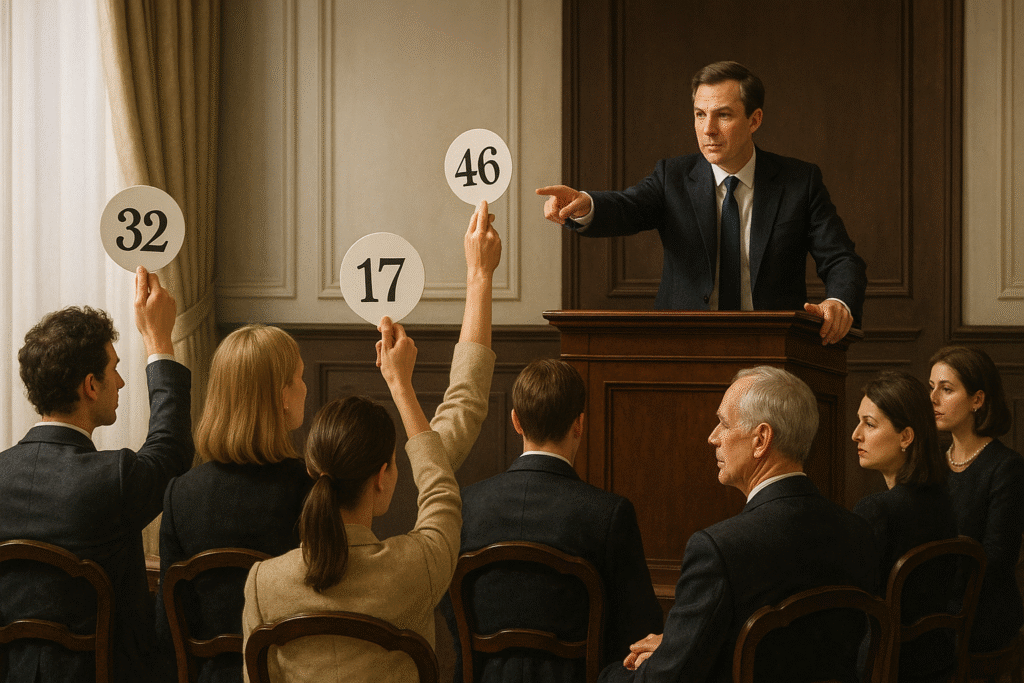

Auctions

Auctions aren’t just about putting a price out there and hoping to be the highest. There are other auctions, such as second-price auctions. Instead of paying the amount you bid, you pay the next highest amount. This causes each bidding party to bid their true valuation of the item, as there is no advantage to overbidding. This format, famously used by Google for its AdWords platform, ensures efficiency and fairness. Advertisers bid on keywords, but the winner pays only the second-highest bid. This mechanism not only maximizes revenue for Google but also aligns incentives, encouraging advertisers to participate without fear of overpaying. By leveraging game theory principles, Google has built one of the most successful advertising systems in history.

Cooperation: Battle of the sexes

The “Battle of the Sexes” is a classic game theory problem that illustrates a coordination dilemma between two players with different preferences. In this scenario, two individuals (often depicted as a couple) must decide between two options, but they have different preferences over the outcomes. For example, one person prefers going to a football game, while the other prefers going to the opera. Both want to be together, so the challenge is to find a mutually beneficial outcome, even though they have different preferences. The dilemma arises because each individual would rather go to the event with their partner than go alone, but they are torn between the options due to their conflicting desires. Whose preferences should prevail?

In the business world, a similar situation can occur in decision-making between two departments or stakeholders with different objectives. For instance, in a company, the marketing and product teams may have different priorities—marketing might want to launch a product quickly to capitalise on trends, while the product team might prefer more time to refine the product. The “Battle of the Sexes” scenario would emerge as both teams seek to align on a strategy that satisfies their core interests, but the challenge lies in finding a compromise where both teams feel they are benefiting from the outcome.

Go study it!

Prisoner’s Dilemma is but a small part of the weird and wonderful world of game theory. I thoroughly encourage you to go out and explore it – the complicated back-and-forth nature of the subject is something that will likely frazzle, yet enlighten.